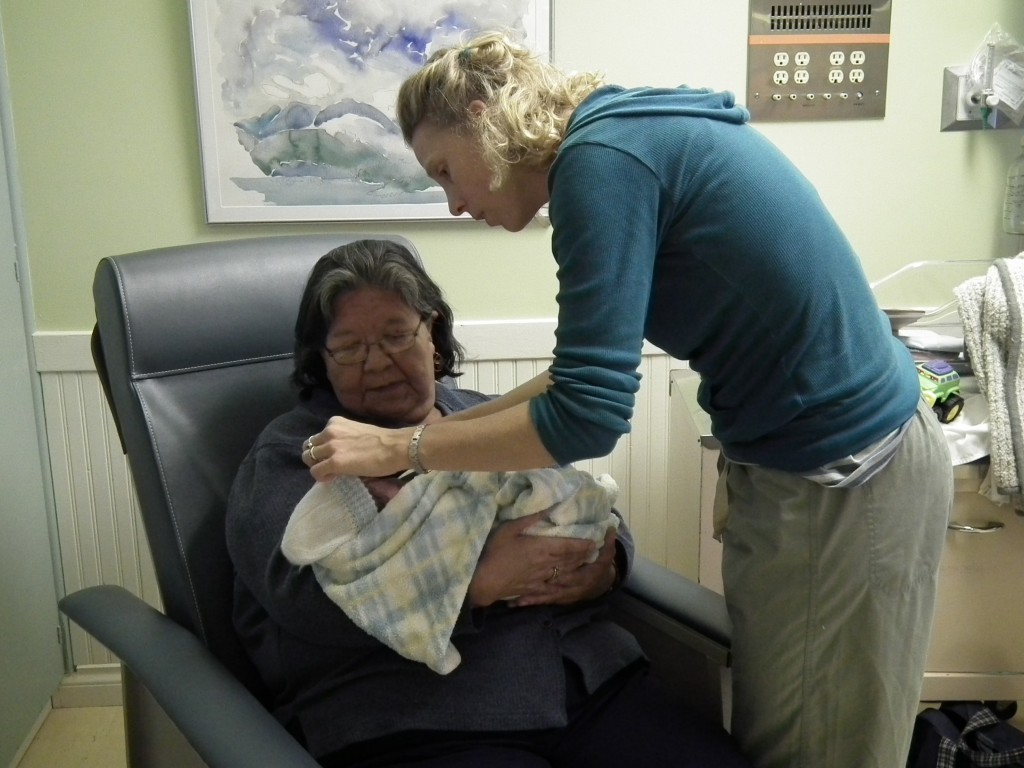

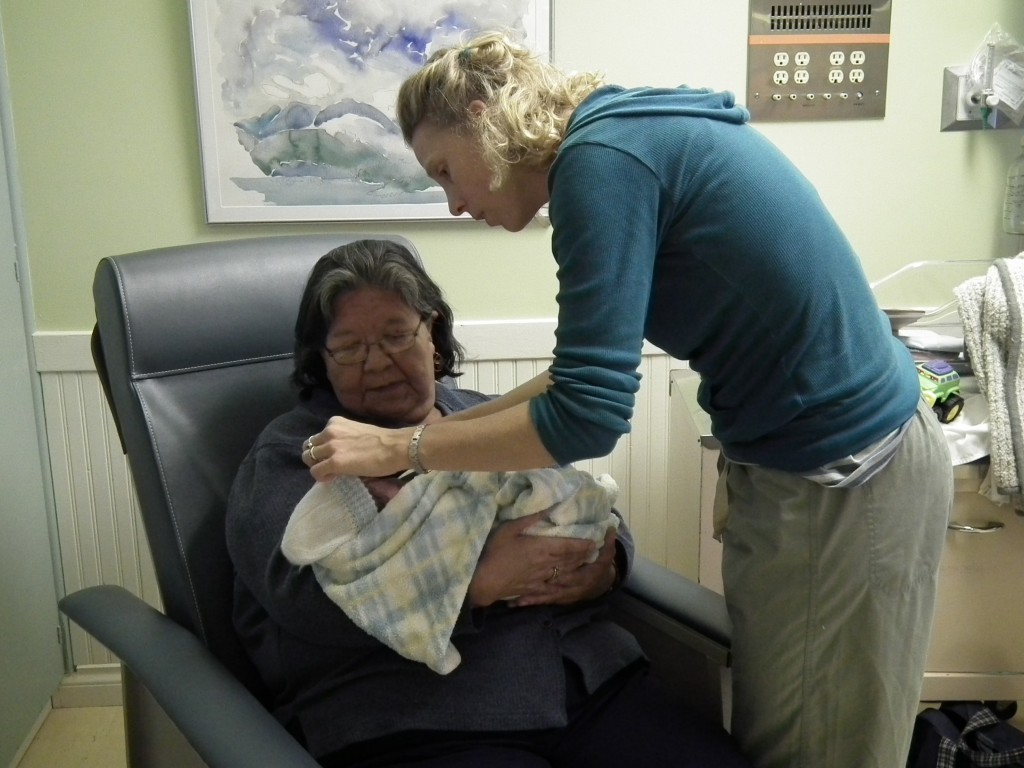

Celina Laursen (right), helps a new mother and her child.

When Celina Laursen left her small, close-knit community on Haida Gwaii to pursue her Degree in Midwifery at UBC, her goal was to give women the choice to birth on the Island. Any way you look at it, UBC Alumna Celina Laursen has achieved her goal, increasing the number of births on Haida Gwaii by more than double prior to when she became a registered midwife.

Laursen filled a significant void in her community on Haida Gwaii when she returned home from completing her degree in Midwifery at UBC in Vancouver. She now assists with approximately 20 births per year, providing almost all prenatal and post partum care on the island. Caesarian back up is not available on the island, so women must still travel to Prince Rupert should they require surgery.

Laursen made her decision to pursue midwifery with incredible timing. Michele Butler, a non-registered midwife on Haida Gwaii, was wrapping up her practice and inspired Laursen who was considering midwifery training. Around the same time, several doctors moved to Haida Gwaii on a more permanent basis. The support that comes from a stable physician base has been invaluable to Laursen and perhaps even essential to her success in the region. Laursen and the physicians on the island work in a College of Midwives of British Columbia-approved shared-care model. They discuss and review all cases and share thoughts, information and concerns about women and their families related to pregnancies and postpartum. The physicians are also available at any time for all on-Island births to provide prenatal or postpartum care and back-up as needed. “Midwifery is a collaborative model, particularly here on Haida Gwaii,” says Laursen. “We need to work together, and with such low volume in each individual community, that means working together island-wide.”

Working with a shared-care model with local physicians has worked extremely well on the island, however Laursen points out, “Each community on Haida Gwaii, like other BC communities, is unique unto itself. Every place has its own populations with their own needs. They have their own cultural contexts, ideas of risk and ways things should be done. There is not one model for all communities.”

Equally important to her success is the support of her family, the community, and the network of midwives in BC. “All the midwives are so thankful to be able to consult with one another,” says Laursen. UBC Midwifery connected Laursen with faculty members and classmates whose support didn’t stop after graduation. Many of the faculty members still check in with her, and she is incredibly grateful for their dedication to students, the program and the profession.

When Laursen isn’t working with women on Haida Gwaii, she is doing locum work out of the South Community Birthing Program in Vancouver or working in other remote communities such as her most recent locum in Inukjuak in Nunavik. Her experiences in the north have helped her gain insight on how other communities handle pre- and post-natal care without the full medical support system of a metropolitan area. There are few remote midwifery practices in BC, so learning from other communities outside the province has been valuable. Some of these communities have had midwifery without caesarean surgical backup for more than 20 years.

Learning from other Canadian midwives has helped Laursen in her practice, but a trip to Africa as a student at UBC had the greatest impact on her professional development. Learning emergency skills at UBC and then actually applying some of them in Uganda with very few resources was an invaluable learning experience. Working with strong Ugandan women who laboured without medication and very few interventions allowed her to gain a true understanding that birth works without all the interventions. However, when there are true emergencies, she is thankful that in Canada so many options are available to birthing women.

When Laursen was attending classes at UBC there were even fewer rural or remote BC midwifery practices than there are today, and many still had surgical back up available. All students learn the proper skills to handle emergency situations, but some of the issues that come up when you are working as a solo or shared practice midwife in a remote setting are difficult to deal with at first. To give back to UBC Midwifery and the larger midwifery and community, Laursen sat on the Rural & Remote Aboriginal Committee and provided feedback on how to include more training on these areas in the curriculum. Laursen’s goal for the future is to increase access to maternity care particularly midwives into rural and remote communities. Right now, no BC communities north of Prince George have access to midwives, and some of these communities where there is not a stable maternity network available could benefit the most.

Living and practicing midwifery in a remote community comes with its challenges– long hours, large distances and low caseloads, requiring the midwife to work outside of the area to create a full caseload, and limited access to training. But Laursen loves what she does. She loves her community and the families she serves. Above all, she is pleased they have access to a midwife should they want it; and she looks forward to the further expansion of midwifery throughout remote communities in British Columbia and Canada.